| |

|

|

|

|

This is my favourite part

of the City, I think. Here we are, barely ten

minutes walk from St Paul's. You've left the

corporate monoliths and the multi-nationals

behind. The Barbican and London Wall are close

by, but they are out of sight to the east, and

you can ignore them. Instead, you wander up into

the entirely unexpected intimacy of Little

Britain and Cloth Fair, the charming houses still

largely residential. If I was the kind of person

who did the Euromillions lottery, and I won, you

can jolly well bet I'd be buying one of them.

Betjeman lived here for a while before the charms

of the English upper classes (or at least one

member of them) side-tracked him to Chelsea.

And then the road opens out into the provincial

domesticity of Smithfield, with central London's

last wholesale provisions market on one side, and

St Barts hospital on the other, the

dressing-gowned inmates looking down from the

long balconies.

Smithfield is poised keenly on the edge of

Holborn and Finsbury, but it is still as much a

part of the City as the Lloyds Building or the

Bank of England. International money cannot allow

places like this to survive of course, not so

close to the more obscene markets of Bishopsgate

and Leadenhall Street, so Smithfield Market will

soon go the way of Billingsgate and Covent

Garden. The hospital will survive it seems, at

least for now, a wilful snook-cocking to those

who judge the meaning and imagination of a place

by the price of a square metre of its territory.

And just beside the hospital is the entrance to

St Bartholomew the Great, looking a little like

an Oxbridge gatehouse set among the tall

terraces.

And just as this is my favourite part of the

City, so St Bartholomew the Great is also my

favourite City Church. It is also the biggest

church in the City, but it was once one of the

biggest churches in England. Incredibly, what we

have here is merely the choir and lady chapel of

what was once a vast Augustinian Priory church,

the nave extending westwards over much of the

ground described already in this article.

The foundation was in 1123, and the hospital was

a part of it. The church was 280 feet long, a

little more than half the length of the original

St Paul's Cathedral. In the pious years of the

early 14th Century a long lady chapel was added

to the end of the apsed chancel. Cloisters were

added in the 15th Century. Come the Reformation,

the parishioners were allowed to buy the chancel

from the new owners into whose well-feathered

laps it had fallen, and the nave was demolished -

all except, intriguingly, the western doorway

into the south aisle of the nave, which survives

as part of the current gatehouse. The lady chapel

was sold off for use as housing and workshops,

one of the chancel aisles became a school, and so

on. A tower was added in the early 17th Century

to the new west wall of the former chancel. The

church was too far north for the Great Fire to

affect it.

The 19th Restoration took place in several waves,

The last and most important by Sir Aston Webb who

was working here until the 1920s. Simon Bradley

in the revised Pevsner notes the archaeological

nature of Webb's restoration, so it is always

easy to distinguish restored elements from the

original - as he observes, it is an

intelligent honest solution, though not always an

immediately appealing one. The lady chapel

was brought back into use, the chancel aisles

cleared. St Bartholomew the Great survived the

Blitz pretty much intact.

No City church has the wow factor on entering as

much as St Barts does. Indeed, few churches in

England do, especially on a winter afternoon. As

the cliche goes, the years roll away. The layered

Norman arches, tier on tier, unfold before you

towards the east. An oriel window peeps bizarrely

into the church from the south triforium. It is

all of a piece, and yet somehow so much more than

a piece. If you are lucky enough to hear the

choir rehearsing, especially if it is something

old and English, you will be transported. Around

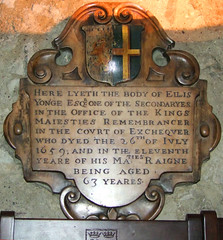

the chancel aisles are post-Reformation memorials

to the Great and Good, but nothing intrudes, for

it would be hard for anything to intrude here in

this wholly majestic and serious space. To the

east is the lady chapel, simpler, full of light

and colour. What survives of the cloisters is now

home to a rather good café.

St Barts is one of just two City of London

churches you have to pay to get into, which in

some ways is a shame as I used to enjoy just

popping in for a few minutes while on my way from

somewhere to somewhere else. But admittance is

only four pounds, less than the price of a pint

in this part of London and easily better value in

terms of refreshment and intoxication. If you

want to take photographs you'll need to pay an

extra pound - think of it as a take-out. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Simon Knott,

December 2015

location: West Smithfield EC1A 7JQ - 1/012

status: parish church

access: open seven days a week. 8.30am-5pm

Monday to Friday, 10am to 4pm Saturday, 8.30am to 8pm

Sunday. Admission £4, photography permit £1.

Commission

from Amazon.co.uk supports the running of this site

|

|

|

|

|

|