| |

|

|

|

|

If a Martian came down to the City and was shown around

the churches of the Square Mile, there is no doubt that

he would think St Lawrence Jewry quite the most

important. This wouldn't be just because of its perfect

setting facing down Gresham Street across the square from

the Guildhall, although of course that would contribute.

And it certainly isn't the biggest of the City churches.

But you step into an interior which is without parallel

in the City for dark-wooded, serious-windowed gravitas.

There is a palpable sense of patronage, of the power of

conservative institutions transformed and transmuted into

brass and banners, into solemn words and ethereal music.

This is a place where the Church of England knows its

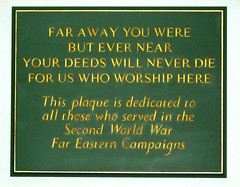

friends, draws a line, and stands firm.And yet, it is all an illusion, for on the

night of 29th December 1940 St Lawrence was completely

gutted by German incendiaries and high explosive bombs.

Nothing survived except for the lower part of the tower

and walls. It was, in its way, the perfect firestorm. It

was a Sunday evening. The churches had been locked after

the services that morning in direct contravention of the

request of the City authorities for buildings to be left

accessible to firefighters. Because it was Christmas week

there were hardly any firewatchers on duty in the area

north of Cheapside. There was a strong wind blowing, to

fan the flames. And as the fires joined together covering

an area of almost fifty acres, the rising heat began to

draw in air from below the flames from all sides. The air

drawn into the furnace was running at more than fifty

miles an hour, and the result was the largest bomb site

in the whole of the British Isles - although nothing to

compare with anything in almost any large German city, of

course.

The medieval church had been gutted

in the Great Fire, and the rebuilding was one of the most

expensive of all the Wren churches. As Simon Bradley

points out, St Lawrence was unusual in that its walls

were exposed on all sides, it wasn't jammed in among

other buildings, and so attention had to be paid to the

exterior. The facing in Portland stone added to its

grandeur.

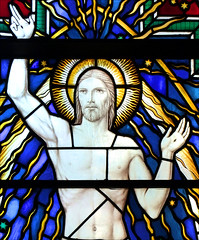

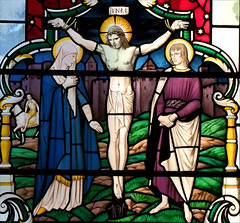

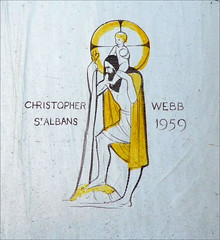

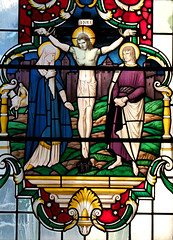

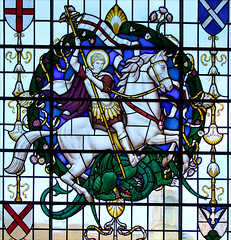

The architect chosen for the

post-war rebuilding was Cecil Brown, with a brief to

provide a church fitting for pomp and circumstance, for

ceremony and seriousness. St Lawrence therefore has none

of the light-wooded Festival of Britain jollity you find

at Lawrence King's St Mary le Bow, or the quiet

candle-lit introspection of Dykes Bowers' St Vedast. This

is church as theatre. Instead of the uplifting thrill of

the John Hayward and Brian Thomas glass at St Mary le Bow

and St Vedast, here Christopher Webb contributed a scheme

which Simon Bradley rightly describes as unobtrusive. But

it all works. There is a great harmony, and a sense of a

church much greater than its individual parts.

Have I made this church sound

unwelcoming? It isn't. Almost every time I've been here

I've found stewards inside, and they are always pleased

to see visitors. And, of course, they have a lot to be

pleased about.

Simon Knott, December 2015

location: Gresham Street 2/035

status: City Corporation church

access: open Monday to Friday, services on

Sunday

Commission

from Amazon.co.uk supports the running of this site

|

|

|

|

|

|