| |

|

|

|

|

Opinions vary greatly as to the merits of this church,

observed Margaret Tabor in her splendid little 1924

volume London City Churches, a review of all

those churches in the City built up to the end of the

18th Century. Some critics point to it as an

illustration of the lack of genius of Wren's pupils...

others find "much refinement" in the north

front, and admire the classical details... The

clanging quotation marks that drop around the words 'much

refinement' probably tell us all we need to know about Ms

Tabor's opinion. The pupil of Wren who was lacking in

genius on this occasion was Nicholas Hawksmoor of course,

who is today recognised as quite the most innovative

English urban church architect of the 18th Century. That

Ms Tabor was not without allies is reflected in the fact

that on several occasions this building has been

threatened. In 1863 an application was made for its

demolition, so that the land could be used for the

construction of Bank underground station. The

parishioners fought off the attempt (in the event, the

station was built in the crypt, and the neo-classical

screen now hosting a Starbucks to the south of the church

was built as the station entrance). In 1919, the Diocese

of London's Commission into City Churches recommended St

Mary Woolnoth as one of nineteen churches for demolition,

the proceeds going to the construction of new churches in

the suburbs.St Mary

Woolnoth's superb location at the meeting point of

Lothbury and King William Street is of course the main

reason for these periodic avaricious attempted land

grabs, but it must be said that over the years there are

many people who haven't really 'got' St Mary Woolnoth.

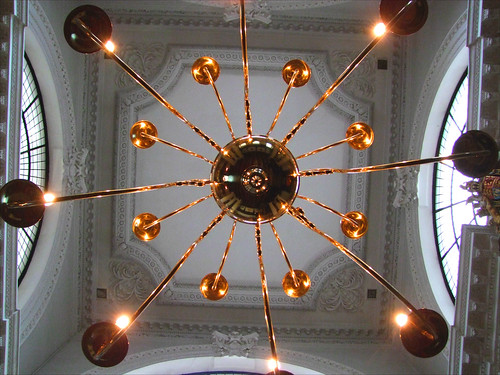

The purity of the Classical form is undoubted - how the

Victorians must have hated it! - but that box of an

interior, unrelenting in its mathematical perfection, is

easier to admire than to love. When the galleries were in

situ and before the high box pews were replaced it must

have been a claustrophobic experience sitting here on a

Sunday, despite the light from above. Sometimes I take

people in here and it blows them away, it takes their

breath away. It doesn't do that to me. Perhaps I, too, am

one of the people who don't really get St Mary Woolnoth.

Quite what TS Eliot thought of it I

don't know, but his own memories of working in the City

which weave their way into his masterpiece, The Waste

Land, recalled the church very precisely:

Under the brown fog of a winter

dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

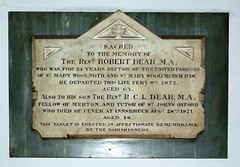

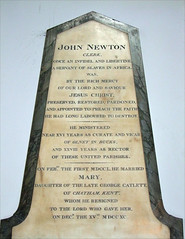

One of the rectors here at the end

of the 18th Century was the hymn writer John Newton.

Newton had been a slave trader in an earlier part of his

life, but repented and became a vocal opponent of the

trade. He is buried here, and his epitaph, although fully

in the language of early 19th Century pious memory, is

still rather moving: John Newton, clerk, once an

infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa, was

by the rich mercy of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ,

preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the

Faith he had laboured long to destroy.

Simon Knott, December 2015

location: King William Street 4/047

status: working parish church

access: open Monday to Friday, services Sunday

> >        > >

Commission

from Amazon.co.uk supports the running of this site

|

|

|

|

|

|