And then there were my great-grandparents, of whom I knew nothing - except one of them, who I could remember meeting when I was very young, for she died when I was six. I could see that she had been born in Dry Drayton. I knew her maiden name, and, finding her parents living elsewhere in the village, I found that they too had been born in Dry Drayton. Her grandmother, who was still alive, had been born in Dry Drayton.Her daughter, who would be my grandmother, had also been born in Dry Drayton. I wondered what it would be like, growing up and living as a poor farmworker in what was by now a rather characterless commuter village, generation after generation.

My Dry Drayton-born grandmother was the grandparent I knew best, so I started poking back through earlier censuses, to find the story of her mother's generation. I expected it to be the story of poor, contented agricultural labourers, working hard for not much money and going to church on Sundays. What I found was quite different. For a start, the family had run a bricklaying business (as had, quite separately, another of my ancestral families). Of my great-grandmother's brothers and sisters, three had gone to live and work in the industrial slums of south London, and they had never returned. One had gone to the Midlands to become a coalminer. One, a soldier, had gone to India. And another, the youngest, had been killed in the first few minutes of the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Well, I was hooked, as you can imagine. I was aware of the temptation with family history to try and follow the male line back as far as possible, perhaps even into the Dark Ages, although you don't need to be a genealogist to realise that the further back you go, the less reliable the data gets. Also, every single one of my eight great-grandparents was from a poor working-class family, and these are the people who successfully disappear under the statistical radar once the insistent census enumerator has stopped knocking on the door. And in any case, what interested me more was the story of those eight great-grandparents, and the families of their parents, the sixteen families of my great-great-grandparents. This would take me back to the very end of the 18th Century, before civil registration began in 1836 or the first census to name names in 1841, but recent enough for the data to be plentiful and reasonably reliable.

The First World War also loomed large. At least five of my direct line ancestors were killed in the conflict, including two in the Battle of the Somme just six miles and twenty days apart. And back in England, villages that I had barely heard of became touchstones, and I visited them with excitement, and had the frisson of finding the graves of direct line ancestors in three of them. More than thirty Cambridgeshire parishes, and almost twenty in Kent, have my direct line ancestors in their parish records. And yet, because they were so poor, sometimes no other record remains. Dozens of my ancestors are in the Dry Drayton parish records back into the 16th Century, but there are just two graves in the churchyard which remember their names.

I had always grown up thinking of Ely as the home of my family, and searching the parish records and censuses emphasised this. Three of my sixteen families had been in Ely since the sixteenth century, and others would join them. In the poor Waterside slums of the 19th Century, every single street had my family names in it.

If this is your first visit to this site, you

might start by exploring my four grandparents,

because that is how the site really began. Their index is

here.

Alternatively,

you might be interested in one of the sixteen

families which formed the goal of the research.

They are my great-great-grandparents' families listed in

order as if from left to right along the top of a family

tree, from my father's father's father's father's family

on one side to my mother's mother's mother's mother's

family on the other.

My father's father's families:

Knott: the story

of the century in and around the Medway towns (my father's

father's father's father's family)

The story of

the Knott family is the story of the Industrial

Revolution. When we first enter their lives they are

agricultural labourers. As the 19th Century progresses,

they leave the fields and go into the factories. As the

Medway Towns grow and merge into each other, forming one

of the world's first industrial conurbations, the Knott

family come there, and for more than a century there they

remain. At first, the Knott men are employed in the

brickfields, and later in the cement factories. As the

industries decline, so the Knott family starts to spread

out into the rest of England.

Bowles: a long

walk through Victorian poverty (my father's

father's father's mother's family)

North

Kent looks to the Thames estuary, and to the open sea

beyond. Although its traditional industries of

brick-making, gunpowder manufacture and hop-growing are

well known, successive censuses show that a goodly

proportion of the inhabitants of parishes like Faversham,

Sittingbourne, Halstow and Upchurch earned their living

from the sea. Although the Bowles name can be traced to

Chilham, near Canterbury, we find them by the start of

the 19th Century living in Sittingbourne and Faversham,

and it is the second of these two ancient towns which

would become the family home. That the Bowles children

who came to adulthood in the late Georgian period were

mariners is beyond question, but popular family tradition

holds that their real trade was smuggling.

Waters: coming

home to the Medway (my father's father's mother's father's

family)

Waters is a

particularly common surname in north Kent, and the Waters

family are found throughout the 17th and 18th centuries

in the parish registers of the adjacent parishes of

Newington and Low Halstow in Kent, although there is no

indication that all the various strands of the name,

landowners and farmworkers, are actually related. My

Waters ancestors are certainly from one of the poorer

branches. But my great-grandfather could describe himself

as an engineer, a cut above the ordinary working classes

in the mid-Victorian period. Engineers were in great

demand during the height of the Industrial Revolution,

and it is perhaps no surprise that a year after their

marriage we find the Waters family living hundreds of

miles away from Kent in the slate mines of north-west

Wales, where he worked as a stationary engine driver,

probably in a quarry.

Harrall: out of

the pages of Charles Dickens (my father's

father's mother's mother's family)

Even today it

is easy to get lost in the narrow lanes of the Hoo

peninsula, despite the proximity of the Medway Towns.

This is the marsh country of Charles Dickens'

novel Great Expectations. When my

great-great-grandmother Mary Ann Harrall was seven years

old, Charles Dickens himself moved to her home village of

Higham. He would have been a familiar sight to the

Harrall family, because he was well-known for wandering

around country lanes, talking to working people. He used

many of these conversations in his novels, and turned

some of those he met into characters. I wonder what they

thought of him? I wonder if any of the Harralls are

disguised among his characters?

My

father's mother's families:

Page: from the

Cam to the Ouse to the Somme (my father's

mother's father's father's family)

The

pretty villages along the tributaries of the River Cam to

the south of Cambridge have now begun to merge into the

city's suburbia, but they must once have had identities

and loyalties of their own. Nevertheless, even in the

late 18th Century the Page family can be found scattered

through half a dozen of them. Over the decades, they

would work their way northwards, the agricultural workers

becoming industrial workers. It is the story of the

Nineteenth Century. My great-great-grandfather was a

stone dresser, and his work must have been in demand in

the 1870s when Cambridge, and its colleges in particular,

were undergoing a building boom. but perhaps his work

took him further afield, because he married my

great-great-grandmother in the Lady Chapel of Ely

Cathedral. It is likely that it was the restoration

project at this building which had brought him to Ely.

Wiseman: the

Waterside's labouring poor (my father's

mother's father's mother's family)

The

Waterside district of Ely was, until well into the 20th

Century, one of the poorest areas of housing in

Cambridgeshire. Four of my sixteen

great-great-grandparents lived and died there, and many

of their descendants were born in the same small group of

streets beside the river, including my father. What

brought the Wisemans from over the border in Mildenhall,

Suffolk, to the Waterside district we will never know,

but they married into the Appleyard family, an Ely

Waterside family of long standing, related to the

boatbuilding family of the same name. The Appleyard

boatyard still exists in Ely today.

Cross: at the

heart of the Waterside (my father's

mother's mother's father's family)

Cross

was the most common surname of all in the Ely Waterside

district of the 18th and 19th Centuries, and while it is

possible to trace my Cross ancestors back into the 18th

Century through the Holy Trinity parish registers, there

is also the opportunity for confusion. I can say for

certain that my great-great-great-great-grandparents were

married in the Lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral in 1828.

Their first child was baptised just six weeks later. It

is even possible that he was born before the marriage.

The father was a labourer, as his son would grow up to

be. They lived on Potters Lane, at the bottom of Back

Hill. Some of their descendants would still be living in

the same street more than a century later.

Carter: workers

from the bleak fen (my father's mother's mother's

mother's family)

The Carter family arrived in the Fens from

Wickhambrook in the rolling hills of south-west Suffolk.

They can be found in the Ely Holy Trinity records, but

they lived three miles out in the bleak fenlands, in the

village of Prickwillow. They were agricultural workers in

what was among the most exposed landscapes of England. In

the 19th Century they would move into the city of Ely to

work in the new agricultural processing factories. It is

the Industrial Revolution in miniature. But theirs was an

abusive family, with a sad ending.

My

mother's father's families:

Cornwell: a Histon

dynasty (my mother's father's father's father's

family)

Histon today is a sprawling northern suburb

of the city of Cambridge, but even in the 19th Century it

was a large and busy village, inextricably joined to the

neighbouring village of Impington. Traditionally a

farming community, it was also the home of the Chivers,

who built their first big fruit-processing factory in

Histon towards the end of the 19th Century. My

great-great-grandfather was born there in December 1819,

and was thus the first born of my sixteen

great-great-grandparents, entering the world when George

III was still on the throne, the year before Queen

Victoria was born, just four years after the Battle of

Waterloo.

Huckle: gone for

a soldier (my mother's father's father's mother's

family)

The large agricultural villages to the west

of Cambridge were home to my Huckle ancestors, and the

family they married into, the Farringtons, whose graves

can be found scattered throughout local churchyards. My

great-great-great-grandfather was born in Comberton, and

travelled a few miles west to get married in Bourn, where

my great-great-grandmother was born. The family soon

moved back to Comberton. In 1841, at the time of her

marriage, her father was recorded as a soldier, but he

was dead before the 1851 census, and buried in Comberton

churchyard. Huckles were still being buried at Comberton

until well into the 20th Century. Remarkably, a

photograph of his daughter survives.

Mortlock: crossing

the Great Ouse (my mother's father's mother's

father's family)

The

River Ouse threads up through the brickfields of

Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire, entering Cambridgeshire

to become the Great Ouse. Beside the river as it enters

the county is Swavesey, where the Mortlock family were

non-conformist millers and farmers in the late years of

the 18th Century. Their name appears in the parish

registers from about 1750 onwards. The name Mortlock is

still visible on Swavesey windmill, and the Mortlock

name, albeit from another strand of the family, is

remembered today in Cambridgeshire by the notorious

non-conformist financier John Mortlock, the self-styled

'master of the town of Cambridge', whose bank was the

first in the city. Even though they were only very

distantly related to him, my Mortlocks were the most

prosperous of my sixteen great-great-grandparents'

families.

Mansfield:

Huntingdonshire's underclass (my mother's

father's mother's mother's family)

In

1815, the year that Wellington defeated Bonaparte at the

Battle of Waterloo and thus the year that the 19th

Century began in earnest, my

great-great-great-grandfather was born

in Needingworth on the border between Huntingdonshire and

Cambridgeshire. In general, the Mansfield family had a

reputation for living outside the law, rarely marrying

and producing illegitimate children at a prodigious rate.

In 1851, a large minority of the inhabitants of the St

Ives workhouse had the Mansfield surname. My

great-great-great-grandfather was not among them,

however, because he had already been convicted of

breaking into a dwelling house, and he was transported to

Australia.

My

mother's mother's families:

Reynolds: out of

Essex, to Cambridge and beyond (my mother's

mother's father's father's family)

In the churchyard of

St Michael at Great Sampford in the gentle clay hills of

north-west Essex there is a line of Reynolds graves, with

three surviving headstones from the late 18th and 19th

Centuries. They were to the families of the brothers of

my direct-line ancestors. The Reynolds were an

established family in Great Sampford, and provided the

village tailors down the generations. But there can never

have been enough work to sustain every member of the

family, and in each generation there had to be others who

were mere farmworkers, and who moved away.

Carter: quiet

poverty in the hilly parishes of south-east

Cambridgeshire (my mother's mother's father's

mother's family)

Wandering

around the quiet, neat churchyards of St Mary, Shudy

Camps and All Saints Horseheath, not far from where

Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and Essex meet, I could find no

mention of the Carter family, or the families they

married into, the Lucases, Alstons, the Parmenters. But

they were here, down the long generations, for the Carter

family feature in the records of these parishes and their

neighbours back into the 17th Century and beyond. Many

families in rural England before the Industrial

Revolution were poor, and many were large. The Carter

family, I think, were poorer and larger than most.

Anable: the long

Dry Drayton generations (my mother's

mother's mother's father's family)

My

great-great-grandparents were both born

in Dry Drayton, and were both from Dry Drayton families

of long standing. Despite the encroachment of Cambridge

suburbia across the fields, Dry Drayton is still largely

rural in character, although the parish does now contain

the large new village of Bar Hill to the north on the

busy A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon road - where,

incidentally, one of my Anable ancestors'

great-great-grandchildren lives with his family. The

Anables lived in the centre of Dry Drayton village, and

the family name first appears in the parish registers in

the 17th Century. Samuel's mother was a Rogers, and his

grandmothers' surnames were Markham and Chapman; these

three family names are found in the Dry Drayton registers

from the mid-16th Century onwards.

Stearn: a quiet

touchstone down the Dry Drayton centuries (my mother's

mother's mother's mother's family)

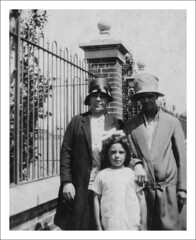

The

Stearn family appeared in the Dry Drayton parish records

for half a millennium, and then in the 1950s they quietly

disappeared. This is what happened to England. And what

else remains of them? One gravestone in the parish

churchyard. The name scattered across genealogical

websites. And yet, I have a photograph of my

great-great-grandmother in the 1930s, her parents already

dead in the Chesterton workhouse, standing in front of

her thatched cottage which no doubt had no running water

and certainly no electricity. All gone today, all gone.

But I am here, and many Stearn descendants come to read

this page. What would she have thought of that, I wonder?